People don’t like it when you point out their mistakes. Admitting something is wrong is painful for many people, creating a condition known as “psychological dissonance.”

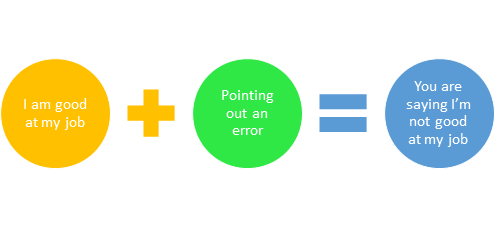

Psychological dissonance occurs when someone is forced to reconcile two contradictory ideas. For example, a person who believes they are good at their job might bristle at evidence that points out a problem with their work product. In their minds, they are a good worker. Good workers do things correctly. By saying they made a mistake, the implication is that they are not a good worker.

Pointing out the error isn’t seen as constructive criticism. It’s a personal attack on their self-identity as a good worker.

This explains why so many people don’t like internal auditors. Auditors exist to question authority. They look for truth and ask hard questions, and people don’t always like the answers.

Why internal auditors make people uncomfortable

This dislike is misplaced. Internal auditors are not the enemy. They are amazingly helpful partners with a financial organization’s best interests at heart. Their goal is not to knock you down but to make you stronger.

Ask yourself: if you were going to take a school exam, would you like the opportunity to take a practice test?

Of course, you would! It would give you the opportunity to see how well you knew the material and what, if anything, you needed to study more before the actual exam.

Would you be mad at the practice test when you got an answer wrong? No. You might be annoyed at yourself for getting it wrong, but you wouldn’t blame the test. You’d appreciate knowing you made a mistake so you can correct it going forward.

Related: Credibility in an Era of Misinformation: Why Audit Is More Important Than Ever

An auditor is just like a practice test. It helps you find weaknesses, so you can improve. It helps your organization become a better version of itself, one that is strong, resilient, and able to stand up to regulatory scrutiny.

Don’t be frustrated when an internal auditor uncovers problems. Be thankful! It may not be the news you were hoping for, but it’s the news you need to hear. It blasts away assumptions and wishful thinking to reveal reality. And it helps support a culture that truly values feedback, which makes an institution stronger.

The dangers of neglecting internal audit

Ignoring internal auditors or not giving them the autonomy and resources to do their job well is a huge mistake that can result in massive fines and unsafe and unsound banking practices.

Here are three recent examples:

- Ignoring auditors. A large mortgage sub-servicer was the subject of an OCC consent order for unsafe and unsound banking practices. What did it do wrong? It fell short when it came to processes for testing preventative controls and self-assessments. The OCC is requiring the board to follow up on deficiencies, including those noted by internal auditors.

- Insufficient audit program (including poor internal controls). The OCC forced JP Morgan to pay a $250 million penalty in 2020 for failing to maintain adequate internal controls and internal audit over its fiduciary business. The bank was called out for having an insufficient audit program and inadequate internal controls that failed to prevent conflicts of interest.

- Not identifying and report weaknesses. In 2019 a hacker accessed one of Capital One’s databases, including the sensitive data of 100 million Americans. When fining the bank $80 million in 2020, the OCC called out the bank’s internal auditors for not recognizing many control weaknesses and gaps in operational risk management. Those they did find were not effectively reported.

Related: 5 Must-Have Elements of an Effective Audit Program

In each of these instances, financial organizations either had bad data from poor internal audit programs or ignored good audit data. If they could go back in time, I suspect these organizations would have paid more attention to their internal audit function and the data it provides.

Want to learn more about best practices for tracking audit & exam findings?